War of 1812 veteran Major Joseph McCormick was already

living along Lake Michigan, in what would become Manitowoc County in 1836, when area Pottawatomie Indians made him aware of lands to the north. He and a party of men ventured north in 1834 to what, years later, became

known as the Ahnapee River. Somehow their sailboat crossed the sand bar at the

river’s mouth and the men reported going

nine miles up-river, as far as today’s Forestville where they named a small

island in honor of McCormick.*

McCormick's party found the richly forested area quite favorable, and

McCormick felt the north side of the river near Lake Michigan would be a fine

place for a city. For whatever reason, neither McCormick nor any of the others returned within the next few years and Kewaunee County was not permanently

settled until June 28, 1851 when John Hughes and William Tweedale brought their

families to make a new home. Orrin Warner followed with his family a week later

and thus was the beginning of today’s Algoma and the permanent settlement of Kewaunee County.

Men had been coming and going in Kewaunee County before

that, however. They were lumbermen. Surveying of what became Kewaunee County

began in 1830s when the flow of the river eventually known as the

Kewaunee was the most prominent feature in the geographic area that would

form the county. That prominent feature was to play a huge part in the county’s

economic development.

|

| Mouth of the Kewaunee River, 1836 map |

Surveyor Joshua

Hathaway and his friends bought large tracts of the heavily timbered land along

that river and around the area that is the City of Kewaunee today. They were

speculating. Hathaway sold water rights to Montgomery and Patterson of Chicago, and in 1837 Peter Johnson was hired to build a sawmill, however the mill owners

failed to provide support during the winter and workers went on foot to Green

Bay, narrowly escaping death, documented in Peter Johnson's letter to Hathaway dated January 12, 1838.. There was a little activity and the unfinished

mill was deserted for six years when John Volk, also of Chicago, became aware

of Hathaway’s search for a sawmill developer on the Kewaunee River. Volk

accepted Hathaway’s offer and work began in 1843. It was the timber during the territorial days that principally motivated the land purchases along that river.

Although faced with significant problems, Volk managed to get the

mill into operation. Lacking a sheltered safe harbor Lake Michigan captains feared being caught in storms. Almost worse was that the timber

had to be floated downstream. Though that doesn’t sound like a big deal, a

constantly shifting sandbar made it extremely difficult to get the logs into

the lake. (At the time, the mouth of the Kewaunee River was east of today’s

Shopko.) When ships were able to load lumber and return with supplies, Volk

learned about other timberland at a place called Oconto Falls about 60 miles north of Kewaunee on the west shore of the bay of Green Bay, and he relocated He didn't stay long, however, and during a subsequent illness, he sold the Oconto Falls land and returned

to Kewaunee.

Volk was joined by his brother and the two built a pier in

1850 or 1851 after earlier, in 1848, rejecting the idea. That meant people, freight,

lumber and, eventually, mail and the development of Kewaunee. Volk once again

left Kewaunee for Oconto Falls but that time his relocation was precipitated by Daniel and James Slauson, relative newcomers to the area.

Though Volks claimed they owned countless acres of timber in the area - and effectively drove others off - Slausons suspected Volk mills were processing

lumber from stands of timber they did not own. When Slausons couldn’t find official

ownership for most of the timber stands at the Menasha Land Office, Volk was

challenged to present title. Since Slausons had filed for ownership

themselves**, John Volk took the easiest way out and sold the mill operation. The

new day around Kewaunee lasted for the next half century.

While they never came close to the operations of Weyerhauser, Knapp, Sawyer, Washburn and other Wisconsin companies existing within the same time frame, by the early 1870s, Daniel Slauson and partner George Grimmer became the county’s largest milling operation. The extent of the timber and what happened is difficult to imagine within today's framework.

While they never came close to the operations of Weyerhauser, Knapp, Sawyer, Washburn and other Wisconsin companies existing within the same time frame, by the early 1870s, Daniel Slauson and partner George Grimmer became the county’s largest milling operation. The extent of the timber and what happened is difficult to imagine within today's framework.

In 1875 the Ahnapee Record pointed to the magnitude of

logging in the camps around Kewaunee saying that within two years time the supply

of pine would be exhausted. The size of the operations can be measured in the approximately

220 jobbers with an aggregate of 500 men that George Grimmer had employed for the

season ending by late March 1875. The 500 men had a proportionate number of working

teams. That same year C.B. Fay & Co. of Casco produced 2 million more feet

of logs than the company anticipated prior to the season’s start. James Slauson’s brother-in-law Charles Dikeman was another large mill operator, operating in Coryville by 1863. Dikeman was

another who greatly exceeded

projections. The paper also said it took about 22 years to reach that

point.

Lake mariner

Abraham Hall was captain of the Rochester, the first boat on record

visiting the lake shore settlements. Before going down on the sands of Two

Rivers Point in 1847, Hall's Rochester was engaged carrying lumber from

Volk's Mill at Kewaunee to Chicago. What

he did after his boat went down is not clear, however in 1849 he was working at

lumbering in Kewaunee. Two years later he was also running a boarding house

there, or at least was allowing the traveling public – few though they were –

to stay the night.

|

| Artist's Conception, ca. 1870 |

Kewaunee County saw

a number of other large sawmills, the largest of which fits into this blogger’s

family history. Just after the Civil War the Scofield Mill at Red River, with its hundreds of employees, had a capacity beyond any other in the county. Scofield had a smaller mill about a mile

south of Dyckesville on a waterfall in an area today called Rock Falls and also operated a larger shingle mill in Door County at what came to be

called Tornado.

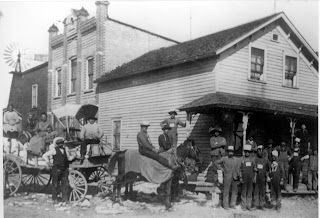

|

| Fellows' Mill at Foscoro |

Taylor and

Cunningham's company was a factor in Kewaunee by the first editions of the Enterprize* in

1859 and Woyta Stransky was not far behind. Red River saw Speer Brothers during

the Civil War and S.G. Shirland by 1872, both on the bay shore, and followed by

Barrette. Interestingly, Surveyor Sylvester Sibley, Guerdon

Hubbard and James A. Armstrong patented land near the mouth of Red River on

September 1, 1835, intending to build a sawmill. By 1840, Wisconsin’s

first newspaper publisher Gen. A.C. Ellis, Green Bay’s Daniel Whitney and

Senator Timothy Howe were involved, but about 1850 Armstrong and Hubbard

abandonded the mill.

There were other

prominent early sawmills in Kewaunee County and at least ten that were destroyed in the

horrific fire of 1871, Edward Decker’s mill was one that was rebuilt. Willard Lamb’s sawmill near Casco at Munchenhof was

another mill that was destroyed in the fire and rebuilt. It began manufacturing

in 1860 and seems to have continued until 1890. Lebfevre at Walhain does not

appear to have been rebuilt.

When Hathaway began surveying in the 1830s, the trees were so thick that it was felt they'd last forever. The density is put into perspective in a story found in Ahnapee Record. Wolf River resident Edward Bacon decided to walk from the mouth of the river to his home near Hall's Mill. Using the river was the safest means of travel but for some reason Bacon was foolhardy and walked, completely missing his home. Some how he kept his wits and walked west where he knew he'd find the bay of Green Bay. When he got there, he turned south toward the place that had recently been named Green Bay. From there he walked the path leading to Kewaunee. Reaching it, he turned north and walked along the lake shore to Wolf River, finally reaching his home several days later. It is written that Bacon's family thought he was dead and was overjoyed to see him. Without a doubt, after Bacon's warm reception, he was dead meat for putting his family into such straits!

The vast stands of timber have disappeared and there are few places where somebody would get lost in the county's woods today. However it might be hard to find one's way out of a herd of dairy cattle. Kewaunee County has close to 100,000 of them. Dairying is the leading industry and the number of cows to people is among the highest in the nation. It was lumbering and its demise and the Fire of 1871 that determined the future, which is what we know today..

When Hathaway began surveying in the 1830s, the trees were so thick that it was felt they'd last forever. The density is put into perspective in a story found in Ahnapee Record. Wolf River resident Edward Bacon decided to walk from the mouth of the river to his home near Hall's Mill. Using the river was the safest means of travel but for some reason Bacon was foolhardy and walked, completely missing his home. Some how he kept his wits and walked west where he knew he'd find the bay of Green Bay. When he got there, he turned south toward the place that had recently been named Green Bay. From there he walked the path leading to Kewaunee. Reaching it, he turned north and walked along the lake shore to Wolf River, finally reaching his home several days later. It is written that Bacon's family thought he was dead and was overjoyed to see him. Without a doubt, after Bacon's warm reception, he was dead meat for putting his family into such straits!

The vast stands of timber have disappeared and there are few places where somebody would get lost in the county's woods today. However it might be hard to find one's way out of a herd of dairy cattle. Kewaunee County has close to 100,000 of them. Dairying is the leading industry and the number of cows to people is among the highest in the nation. It was lumbering and its demise and the Fire of 1871 that determined the future, which is what we know today..

*The mouth of the river now called the Ahnapee was east of the Harbor Inn. The river was dredged and straightened years later by the U.S. Engineers. A 9 mile trip is recorded but Forestville is little more than 5 miles from Algoma. The island disappeared before 1900.

**There are 5 pages of 1854 land transactions representing about 100 parcels involving Slauson.

**There are 5 pages of 1854 land transactions representing about 100 parcels involving Slauson.

Sources: An-An-api-sebe: Where is the River?, c. 2001; Decker Files and Fay Papers, ARC at UW-Green Bay; Here Comes the Mail, Post Offices of Kewaunee County, Kannerwurf, Sharpe, Johnson, c. 2010; Hjalmar Holand, History of Door County, c.1919; Marchant, Les & Jeanne, Marchant

Relatives of Red River c. 1982; Ruben Gold Thwaites Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin; U.S. Government Bureau of Land Management; Ahnapee Record and Kewaunee Enterprize/Enterprise; Kewaunee County maps

Volk's correspondence is a copy an original letter that was in the author's collection which has been sold. Photos and documents are in the blogger's collection.

Volk's correspondence is a copy an original letter that was in the author's collection which has been sold. Photos and documents are in the blogger's collection.