Having spent years compiling an index of significant data

regarding well over 1,300 men Naturalized in Kewaunee County, trends in

required information began to pop out. An index is exactly that; it contains

the names, dates and location of the actual documents. Building a database from the documents

themselves reveals other bits of information, some of it quite surprising.

|

| 1870 Naturalization, Kewaunee Co. |

Actual documents indicate that quite often a Bohemian man's surname was spelled

three different ways on a single sheet of paper. It appears as if the first

name was as spelled on the Declaration of Intent. The second name seems to be what the public official in

charge felt he heard. The man's own signature was another spelling. From the beginning, Naturalization applications generally included the country of birth, and port and year of

entry to the United States, as did the Declarations of Intent. Most documents renounced allegiance to a foreign power.

Gradually the pre-printed documents became more complex, requiring the place of birth and actual date rather than just year. As the documents changed in Kewaunee County, so did such papers in other places. Not all were alike. Occupations were included as time went on. and after Rural Free Delivery came to Kewaunee

County on November 30, 1904, the information included place of residence such

as Rt. 2, Luxemburg or Rt. 6, Kewaunee. Distinguishing characteristics - such as a wart on the

nose – was noted. The wife’s name, the ship, ports of departure and arrival, and

finally children and their birthdays are found in some documents. At one

point, the occupation of witnesses was listed. Dates of the Declarations were

always there, however following the Civil War, Declaration and Naturalization of those who served sometimes occurred at the same time. Before the 1876 plat map, witnesses often

provided a clue to a man’s area of residence.* Sometimes called first papers, a Declaration of Intent to become a citizen was all some

filed. Because the foreign born could vote and own land, many felt those first papers were all that was necessary.

|

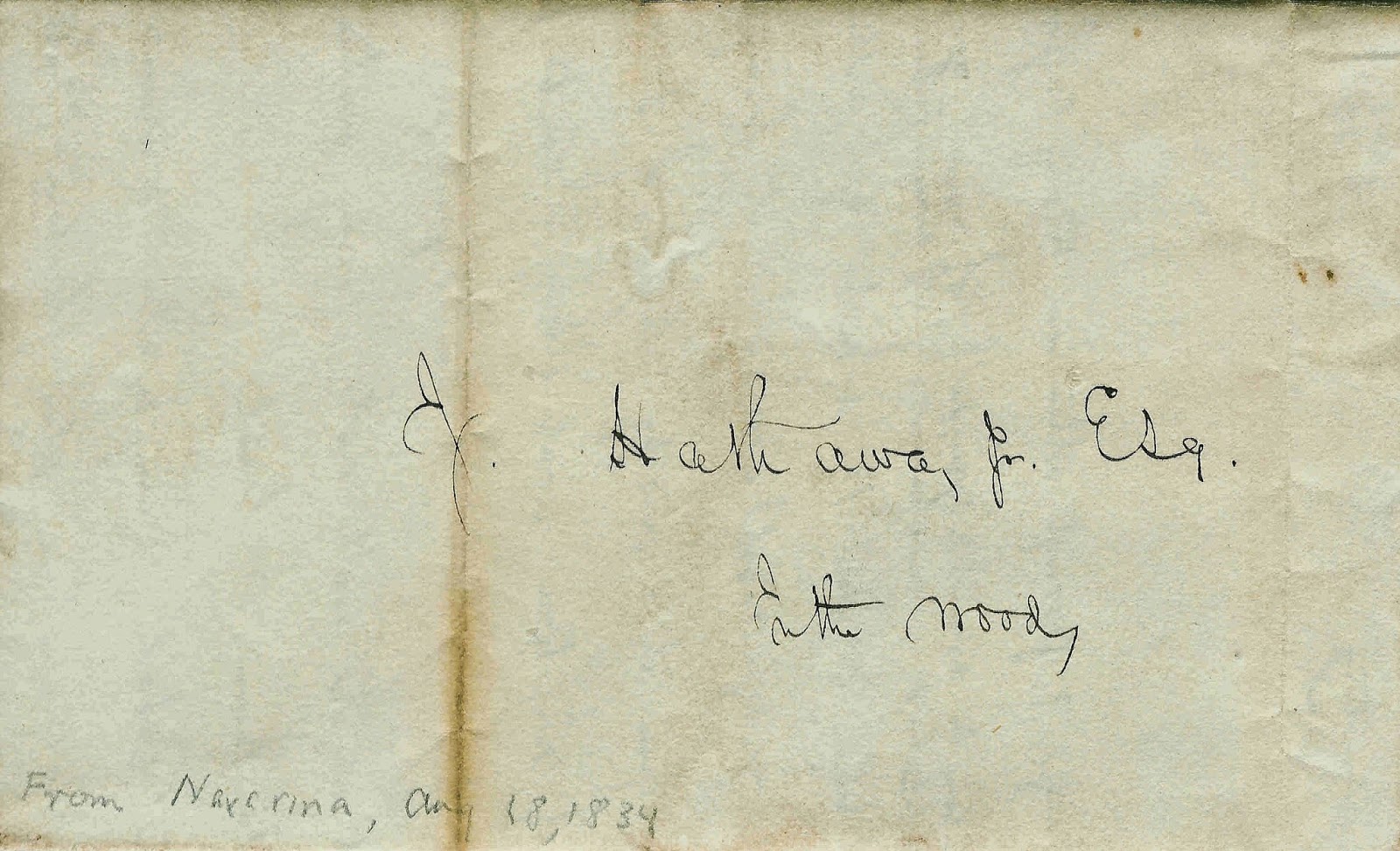

| 1852 Declaration, Manitowoc Co. |

In early 1914, there were some eye openers among many who

felt they were citizens. In compiling the expanded records, a significant number of Naturalization records were found to have attached affidavits from men telling how someone in authority – the sheriff – was at the polls preventing their vote, saying they were not citizens. If the affected were only Germans, one might

think the war eventually known as World

War l that started in Europe the following summer was beginning to rumble

in Kewaunee County, however the affected were Bohemian and Belgian too.

In each case, men including those such as Germans Fred Gaulke, William Hannemann and August Moede

felt they were citizens because their fathers told them they were. Since they were under the age of majority at the time of immigration, they were thought to be Naturalized when their fathers were. Without question men including Charles Zuege, Wenzel Bauer, Peter Seidl and Joseph Bader said they had voted in all elections. Alexander Wautlet, Joseph Gilson and Louis

Villers were among those who had held elected office, serving on school boards,

as road commissioner and more. Joseph

Wisnewsky was another stopped from voting. He said he was Naturalized in Spring

Valley, Illinois. Joseph Pankratz

thought he had been Naturalized 30 years earlier and had exercised the vote all

that time. Others had filed their first papers understanding that gave them

the right to vote. Which first papers did. Why was this happening?

When West Kewaunee men Frank Mach, Herman Feger and Vincent Paul were granted citizenship in 1908, all three had been county residents for a quarter of a century. They all attested to reading the Constitution and their approval of it, and had no "anarchistic or bigamous connections." One could say these men "lucked out." These men had their second papers, their Naturalization documents, and could vote.

When West Kewaunee men Frank Mach, Herman Feger and Vincent Paul were granted citizenship in 1908, all three had been county residents for a quarter of a century. They all attested to reading the Constitution and their approval of it, and had no "anarchistic or bigamous connections." One could say these men "lucked out." These men had their second papers, their Naturalization documents, and could vote.

At issue was a 1908 Wisconsin Supreme Court ruling that

said in order to vote after 1912, foreign born residents had to be full

citizens. The November 2, 1908 Wisconsin

State Journal thought it was clarifying the ruling in saying the changes to the Constitution meant "Persons of foreign birth who, prior to the first day of December A.D. 1908, shall have declared their intentions to become citizens conformable to the laws of the United States on the subject of naturalization; provided that the rights hereby granted to such persons shall cease on the first day of December, A.D. 1912" The Journal could have made it plain and simple if it had written that full citizenship meant that one needed to be Naturalized, or having what was called second papers. It was a ruling affecting thousands of Wisconsin residents, and within the next few years parts of Wisconsin saw a rush to file the papers guaranteeing full citizenship. The rush did not appear to affect Kewaunee County.

Until 1912, men were legally permitted to vote if they had filed their first papers, or Declaration of Intent. Beginning in 1912, men were required to have their second papers or lose their right to vote. If older men such as Wisnewsky lost their documents, it was not an easy task to get a copy from another state. Pankratz thought he was a citizen for 30 years, however there were others who had voted for 50 years before they were denied the vote. Door County Clerk of Court Allen Higgins spelled out the ruling before the 1912 elections when he said those of foreign birth lacking second papers were barred from any election whether it was for school board, town laws, bonding issues or anything else.

Kewaunee County Clerk of Court Carl Andre reminded county residents in February 1913 that Naturalization had to be applied for at least 90 days prior to the upcoming court session, which would be in May. He pointed out that anybody applying needed to bring their first papers and that their petition needed affidavits with signatures of two credible witnesses who were already citizens. A month later the paper carried an article saying full citizenship was necessary for those planning to vote in the spring elections and that anyone having only first papers prior to January 1, 1907 would be turned away at the polls.

Late in 1914 when Door County Judge Grasse offered his opinion, he said the Court could reverse itself or let the original amendment stand. Grasse's advice seemed to be to get the second papers to be on the safe side. Confusion continued because in early January 1915, the Supreme Court said the 1908 amendment was improperly passed and that thousands who had been dropped from the poll list could now vote. That included about 75 Algoma men.

The Naturalization applications following the Court’s initial

decision tells us a great deal about Kewaunee County. Affidavits were several

paragraphs, some of which were essentially the same. Others contained

additional information, but each man felt he was a citizen with the accorded rights and privileges. Some had

fought in the Civil War.

Looking at Kewaunee County Naturalization, it would

seem the county reflected the state. The Record

mentioned the number of Algoma men stopped at the polls, but how many men across the county

were affected is unclear. At least 27 signed an affidavit applying for and

achieving full citizenship. The 1908 Amendment was publicized so men should have been aware of it even though language barriers still existed. One would think a rush within the county would have

occurred after that date, but a review of Naturalization dates indicates that for some reason it

didn’t happen. Few Naturalization occurred between 1908 and 1914, however

8 or 10 men were awarded citizenship in 1914 without the affidavits, which suggests they were not stopped at the polls..

Looking at Wisconsin’s immigrant population, the 1908

Amendment and its 1915 reversal, and the events in Europe, one wonders about

political expediency. There is more to the story.

*1876 is Kewaunee County's first existing plat map. There is another indicating it is Franklin 1858, however the map was platted by a 4-H club during the 1960s using land records.

Sources: Algoma and Door County newspapers;Wisconsin State Journal; Kewaunee County Declaration and Naturalization indexes and Naturalization documents to 1920 found in the ARC at UW-Green Bay. Documents are from the blogger's family history.

*1876 is Kewaunee County's first existing plat map. There is another indicating it is Franklin 1858, however the map was platted by a 4-H club during the 1960s using land records.

Sources: Algoma and Door County newspapers;Wisconsin State Journal; Kewaunee County Declaration and Naturalization indexes and Naturalization documents to 1920 found in the ARC at UW-Green Bay. Documents are from the blogger's family history.