Today’s Algoma is a faith-filled community, many identifying

with one of the area church congregations. The community was Kewaunee County’s

first permanently settled place during the week that ended on July 4, 1851. Early

settlers’ religious needs were met by itinerant clergy known as circuit riders,

and congregations organized quickly. In 1858 a Lutheran church was built on the

north side of the river. Catholics organized the following year and built a

church in 1863. A German Methodist Episcopal congregation was formed on the

county line in 1861 while Methodist

church was built at 4th and Fremont in 1863. In 1873, the Baptists had organized and were meeting on 3rd and Clark, By late 1874, it seemed - with the exception of the Episcopal church which had yet to be organized - they were all building.

Althought it was Abraham Hall who instigated the Baptist congregation, it was the blind preacher, Rev. George P. Guild, who did the organizing. The

small congregation was made up with many of those credited with much of the

community’s early history. The small congregation that disbanded in 1894 brought

“trouble right here in river city.”

Trouble in Ahnapee’s fledgling Baptist church turned to

scandal in May 1881 when the remaining congregation wanted financial reports

following the departure of the minister. Where was all the money raised for the

Union Church that was never built? Membership was unable to get satisfaction

regarding finances before the first minister left. Distrust followed his successor,

and depending on which story is to be believed, the congregation was

on-again-off again for years until it finally disbanded in 1894. Animosity

affected townsfolk whether they were members or not, and it remains unclear if

the financial matters were ever sorted out.

Ahnapee’s Baptist congregation was organized in 1873 by Rev.

George P. Guild who immediately led the efforts to build a church that stood at

3rd and Clark Streets. Church women’s groups worked tirelessly over

the years to raise funds through oyster suppers, maple syrup events, Christmas

bazaars 4th of July festivals and more.

Rev. J. Banta was serving the Methodists of Ahnapee and

Carlton when Guild came to begin his Ahnapee ministry. In March 1974, Banta ran

a logging bee on itinerant minister Hela Carpenter’s land to cut timber for the

new Ahnapee Methodist church at 4

th and Fremont. The April 16, 1874

Record quoted the

Milwaukee

Christian Statesman’s interview of

Rev. J. Banta who

told about those in Ahnapee and Carlton crying for the love of God and

forgiveness, desiring salvation. He told about the numbers baptized at both

places, some who had been in habits of drunkenness and tippling. Banta said the

Baptist brethren at Ahnapee were having good success under the leadership of

Bro. George P. Guild, a blind pastor who was aided by his wife, laboring in the

Lord to save the place. It sounded as if Ahnapee was a den of iniquity. The

Catholics and Lutherans of the place were not mentioned, however those

congregations were organized nearly 15 years earlier. Interesting as it is, the

Methodist Rev. Carpenter filled in for Baptist pastors.

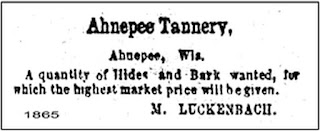

The adjacent picture post card from the blogger's collection predates the 1937 fire that destroyed the building, the once Baptit Church at the southwest corner of 4th and Fremont.After a ministry of about five years, a May 1878 the Record

noted Rev. Guild was in town visiting before leaving for his new home in

Portage. Having resided in Ahnapee for about 5 years, the paper noted his

accomplishments in building up the church to the point where it could sustain a

pastor, an attraction for drawing a new pastor. Guild was wished well as he

went on to serve as a general missionary in Wisconsin.

A year and a half later, October 1879, former Ahnapee pastor

Rev. Guild led the Wisconsin State Baptist Anniversary at Fox Lake. Untiring

efforts in Ahnapee were mentioned. The Standard, a religious paper,

mentioned Rev. John Churchill of Ahnapee, who followed Guild, while saying

there was no Baptist preacher between Ahnapee and Milwaukee. That paper said

the poor people in the “new country” were without preaching for years. The

paper told about Churchill’s trip in the northern part of the peninsula where

he walked nine miles to and back for an appointment, the mention of which

“touched the hearts” of the ”good sisters” who began raising funds for a horse

for Churchill. At the close of the convention sermon, “Brother Churchill” was

called forward and presented a cup filled with money for the purchase of a

horse. Brother Churchill said he felt “his cup had runover.” By October 1879,

the Baptists were meeting in a new building at the southwest corner of 4th

and Fremont, now the site of Algoma Public Library.

When Guild arrived in 1873, he found 9 Baptists from Ahnapee

and one from Kewaunee. He baptized 27,

and 16 more joined by letter. Eighteen of them either left the church or

died by the time Guild was leaving town. The first serious trouble came when

remaining congregants wanted a financial report. But Guild left and members never

got one.

Controversaries within the

Baptist congregation exploded during 1881, when the Record published

a letter, signed by one who called himself/herself “Justice,” taking issue at

goings-on at the Baptist Church. The letter pointed to the blind preacher, and

to accuse a blind preacher of corruption within the church was something few

would do. The facts – at least as they were known to be by author of a letter

to the editor - were carefully laid out in a series of missives. The paper

called the affair a “confidence game.”

Justice’s information came from a trustee and one who served

on the building committee of the “Union Church.” The church was called a

failure although the trustee disputed “failure.” In the year 1862-63

Presbyterian Elder Donaldson periodically preached in the schoolhouse. Ten

years later the Baptist edifice was built. Area population was small, times

were hard, money was scarce, and because there were a few Presbyterians, a few

Methodists and a few Baptists, the proposition was made to build a Union

church. Within a half hour, enough money was raised to build a church estimated

to cost from $800 to $1000.

In mid-May 1881, Baptist Church treasurer William Hilton

wrote a letter to Mr. Barnes, editor of the Record, disputing what he

called a malicious letter from “Justice.” However, Hilton did write about the "hypocrite preacher who prays and takes opportunities to pick pockets." He called

the preacher a sneak thief and said the Sunday school was better before.

Hilton pointed out the scarceness of money and the decision

to build a Union Church for Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians, but said the

Methodists cancelled their representation in the Union Church and wanted to

abandon the idea when W. B. Selleck said he would donate a site to the

Methodists and personally pay what could not be raised to build. The Union

Church organizing ended and subscription papers were burned.

Hilton said the monies raised had gone into the minister’s

pocket and there was no accountability. Hilton said he did not care how the

pastor spent his own money, although charged him with immorality and dishonesty

which was an “open secret” in Ahnapee. The preacher left when there were only 8

active members left, going on to cause more trouble, and Hilton felt there was

“honor among thieves” as a “Christian virtue.”

Hilton also claimed Guild failed to keep records. He said

Guild never built a church and that folks were dissatisfied because he had no

energy. Guild was said to build a house with some of the money, and when Hilton

accused him of stealing church money, there was no denial. Hilton questioned

money he was owed by Guild who said Hilton’s money got credited to A. Hall

& Co.

Guild left and was replaced by Rev. Churchill. In April 1881,

it became known that Rev. Churchill was resigning as pastor of the Baptist

church although some wanted to retain him as an evangelist. The Guild accounting spilled over to Churchill and there were questions in the congregation, such as who would control the church and

whether divine services would continue in the building. Churchill was engaged

for another 6 months and at the first evening service following the

re-engagement, he gave his reasons for staying while he had fully intended to

leave. He said he remained not to cause discord, but because he had agreed to

stay for a specified sum and felt it was wrong not to accept the call.

By mid-1881, Abraham Hall's brother Simon Hall got into the act, casting slurs on

the character of “Public Sentiment,” another of the writers to the paper.

Editor Barnes took issue with Mr. Hall waging war on a private individual who

wrote on behalf of an outraged community. Barnes said the paper wanted to be

“counted out” in the private warfare among citizens and continued saying that

every communication in support of the preacher “simply adds another nail to his

coffin.” The paper went on saying, “Truth is mighty and will prevail, therefore

if he is innocent the fact will be established in due time and his friends need

not tear their hair on that account." Barnes said the paper was not prejudiced

in the matter but did have the welfare of the community at heart thus would

always labor for protection of the right and suppression of the wrong.

Hall said the former pastor elevated the moral and religious

standing in the community. Hall questioned the credibility of Public Sentiment

while hoping Editor Barnes would not throw his letter in the waste basket. Hall

said he was not a member of the church and had no religious ties with it.

Public Sentiment said $8,000 was raised for a new church

although Hall declared he got copies of the subscriptions and a total of 34

people donated $1,238.75, but not all in cash. The balance was paid in material

and labor, but what is the value of that, he asked? Hall understood the Ladies’

Christian Association contributed a large amount, making the total about $1500.

He felt it was the untiring work of the ladies and the perseverance of the

blind preacher that built the church. According to Hall, the church was built

under disadvantages when contributions of labor and material could not be

obtained when wanted. There was no competent master mechanic to direct the

labor, therefore parts of the interior were torn down and rebuilt. A lack of

funds, labor and materials called for the necessity of building paper, also

called tar paper. Hall said the church was built piecemeal and went on to

list expenses and sources of payment. The Methodist, Episcopal and Lutheran

churches were built with the same kind of contributions, many in contributions

of material or labor. Costs were excessive for the Baptist church, but

it was the swindling. When Guild left, the congregation gave him a

recommendation. Nobody questioned anything until he left town.

Hall called attention to more than blindness, saying Mr.

Guild had an invalid family to support while his health was in decline. He

thought the preacher had more friends after the “tide of calumny” than before,

however if there were charges, they needed to be brought forth and dealt with.

They were wounding an already inflicted man.

Early in May 1881. Rev. John Churchill had served the

Baptist church for three years when he said he was giving his last sermon. The large crowd paid

close attention, rather than the usual whispering of the young, which said the Record,

was ill-breeding and bad manners. Churchill’s text concerning every man’s work was

taken from 1st Corinthians.

Churchill discussed responsibilities of a minister and his

flock, pointing out that every minister’s work would stand the test of time set

forth in scripture. He acknowledged his resignation because of the differences

in opinion on the transactions connected to building the church. It was

impossible for a divided church to be successful. Christian churches owe

fairness to their sister churches and when he became pastor, he was given to

understand there were 45 members with a church that cost $4000, but he couldn’t

see where the money was spent. That the church was misrepresented was unfair to

him. The congregation felt it could not raise money to keep the pastor on, but

they hoped he could serve other denominations.

When a May 26, 1881 letter to the editor was written, its

author questioned the information from the preacher saying only 34 of the 800 English

speakers in Ahnapee and the area contributed toward the building. The church

itself had 53 members when the pastor left, prompting the possibility of over

one-third of the members not contributing anything. It kept going. Churchilll lacked information.

The letter’s author claimed to have a list of over 200 who

donated, some several times, though he knew his list was incomplete. The

author said the preacher (Guild) failed to keep records while doing the

collecting and spending himself. While Guild – referred to as Simple Simon –

said he collected $193 in cash, the author had concrete evidence that at least

$1300 was donated, however it was felt the total was more like $1800-2000. It

was shown that the church was $500 in debt while pointing out that vouchers,

treasurer’s reports, and so on had disappeared. Contention was that the fraud

bilked other churches out of money because those of other faiths charitably

offered monetary assistance for the Union church.

The letter writer identified himself as “Public Sentiment,”

reflecting the outraged and swindled public who had the “right to ventilate the

rascalities of a dishonest, lecherous old fraud” who pretended to fulfill the

gospel. Furthermore, “Under the guise of his sacred calling, he has swindled

men out of their money under the pretenses of building a church, and entered

the homes of our people and insulted unsuspecting women.”

Public Sentiment said the public press was right to expose

the duplicity of the minister – a public man – who set himself up as a teacher

of morality and religion, and thus thought he was excused from accountability

or criticism. The minister countered with his integrity being questioned until

he left Ahnapee.

It was said there were substantiated charges in Milwaukee as

well, however they were suppressed because of politics. Public Sentiment felt

the Guild left Ahnapee because he couldn’t steal anymore and that it was

getting “too hot” for him.

While money was raised in every conceivable way, Public Sentiment felt the exact cost of the Baptist Church

would probably never be told. When

“Simple Simon” left, the church was not finished and the “discordant and unharmonious” membership was left with a $500 mortgage and a floating debt of $200.

The Guild animosity kept on going and nearly spilled into

the Enterprise which made it known in June 1881 that it received a

letter about the “Baptist muddle” in Ahnapee but would not publish it.

Rev. Churchill seemed caught

in the middle and, no doubt, had it when he gave his second farewell

address in mid-July 1881. Churchhill again based his remarks on Corinthians - this time 2nd - the 14th

verse of Chapter 13. The paper said though the remarks were

brief, they were well chosen and commanded strict attention. It went on to say

he was leaving in a spirit of good-will and would probably permanently settle

in Iowa after a stint in Sheboygan. Those sorry to see him leave Ahnapee felt

at least he would no longer be venomously attacked as the target of

unscrupulous acts.

By 1894, the congregation had

disbanded and its building sold to Hanford Hall who turned it into a hotel

known as the Dormer House. For a time, it was used as a furniture store before

becoming Door-Kewaunee Normal School. The building was destroyed by fire and rebuilt. In 1972, the building was sold to the City of Algoma and is

currently used as Algoma Public Library and city offices including the police

department.

1950s postcard of Door Kewaunee County College; now Algoma's municipal offices' center

Sources: Ahnapee Record, An-An-api-sebe: Where is the River?, Commercial History of Algoma, WI, Vol. 1, Kewaunee Enterprise. Postcards are in the blogger's collection.