While discussing the amount of coal resources in the U.S.

several years ago, then President Barack Obama said the U.S. was the Saudi

Arabia of coal. The Hopi Indians were using coal to fire pottery in the 1600s

and it was coal that led to industrialization in the U.S. and across the world. Coal became a necessity in

Algoma too.

Necessities and resources breed strikes, and the coal strike

early in 1900 had an impact on Algoma, although not nearly as the strikes that

followed. Things were changing. Coal was important to blacksmiths in the small community, and some

residents had small coal-burning stoves, but coal was most essential in the

production of iron and steel in the eastern states. Trains and ships were

burning coal, and coal was used in the generation of electricity. As the U.S entered the 1900s, coal became more important, and

then it was anthracite which burned hotter and so much cleaner than the

long-used soft coal.

The United Mine Workers of Pennsylvania struck for shorter

work days, higher wages and recognition for their union. Cities across the

country were depending on coal and, with winter coming, the coal strike could

have been more disastrous than it was, at least in Algoma. It was a first in

that the strike was the first time the U.S. government had a presence in

arbitration. President Theodore Roosevelt set up an investigating commission

that suspended the strike. In the end, workers increased their income by about

10% and had their work day reduced one hour, going from 10 to 9 hour days while the mine owners made more money and never did recognize the union. Bituminous coal

workers who went on strike before 1900 made gains the anthracite workers did

not. And it was anthracite that was growing in popularity.

Initially, it was Ahnapee & Western that brought coal to

Algoma, and not always without incident. In June 1900, the city saw about 30

tons of coal dumped on the foot of Steele when a boxcar jumped the track. As it

was, the train was run into the side-track where the crevices were filled with

accumulated sand and gravel, derailing the back of the engine. It took the crew

about three hours to right the car, but how it dealt with the piles of coal is

anybody’s guess. Presumably because of what happened the following day near

Kewaunee when three carloads of coal were lost. The accident was far worse. A

washed-out culvert 6 miles from Kewaunee caused the locomotive to jack-knife. Two

railroad employees died in the tragedy.

While Kewaunee County seemed to be coping with the strike, New

York papers said in June 1902 that coal was overshadowing trade because of less

than favorable manufacturing. The papers continued saying that idle miners

would be available to take temporary jobs in Wisconsin or other states that

needed temporary farm workers. By November it looked as if the government would

use prison labor, something that didn’t happen but nonetheless stirred up a

hornet’s nest.

Papers were full of mining, what was going on in Washington,

and even around the world. Local papers carried the national news, but also

kept an eye on local happenings. It was news in July 1902 when reports were

that part of Sturgeon Bay’s Hart Line coal dock broke down thus dumping large

amounts of coal to go into the bay. News was also made when the Furniture

Factory received a carload of soft coal

at the same time. The company had been using wood, but the wood supply became

so scare that the company was forced to use the soft coal. It seemed as if the editors were getting tired of the

strike, saying ”every person in the county will rejoice over the ending

of the strike, unless a there were a few selfish politicians who hoped to

profit from its continuation until after the election.”

In October the Record opined that the householder trying to

conserve his coal stock would be well-advised to put storm windows on his

house. Estimates were that storm windows saved 1/4th the cost of

fuel. In December one of the trappers dismissed the coal trusts saying they might

as well as go out of business because, to look at muskrats, the winter of 1902-03 would be one of the

finest. When swamp muskrats made their homes large and warm, it was a warning

that weather would be bad. The trapper’s prediction of an easy winter was that the

muskrat residences were small and thinly covered, meaning a mild winter would follow.

Local papers called little

attention to lack of coal in town and how folks were affected, however found it

newsworthy early in 1903 when a train carload of coal came from Green Bay for

the school. By then the editors were writing that although hard coal was

thought to be a failure of usefulness in tests just after 1800, 100 years later

the coal was so useful that it “ruled the human race.” It seemed to suggest

Algoma needed that coal too.

When the coal strike ended

later in 1903, Algoma was breathing easier and expected to have enough coal

within a month. In December the editor said that the cold weather was affecting

wood and coal piles, but Algoma was fortunate to look toward keeping warm with

plenty of both. Things began happening in Algoma, and coal began its rule there

too. In September 1904, William Hobus finished the new coal shed for the Water

& Light plant. The shed was big enough to hold four carloads of coal. Coal came via the railroad

and via coal ships, which sometimes created transportation problems.

Newspapers saw such

issues as a win for farmers in Eastern and Northern states such as Wisconsin.

Coal influenced prices paid for wood, and years after the strike farmers were

advised that their own cordwood would turn a profit while keeping the woodlot

productive. They could also provide their own fuel. Low quality woodlot

products never brought in much money, but the year offered farmers the

opportunity to get rid of less productive trees while improving woodlot

condition.

It almost seemed to happen

magically that by late 1909, Algoma had the finest coal docks around. In April,

Henry Grimm of Algoma Fuel Co. announced a new project that would make Algoma

the coal distribution point for an entire section of the country.

Grimm had an architect in town, dealing with plans and specifications,

for a new coal dock to be built on the company’s property on the north side of

the river. The dock would include such modern details as a steam hoisting

device.

Michael Wenniger, Sr. was in charge of construction when the

Fuel Company began building its new dock, in 1909, on the north side of the

river at the west end of the north pier. A week before the first ship was

expected, a Green Bay engineer was in Algoma starting up the machinery and ensuring the hoisting apparatus would work without a hitch when the boats began arriving. After a few minor defects were dealt with, the equipment was ready to go. A 40 x 60’

coal shed 30’ high was being rushed to completion at the same time. The shed stood

about 130’ north of the river.

|

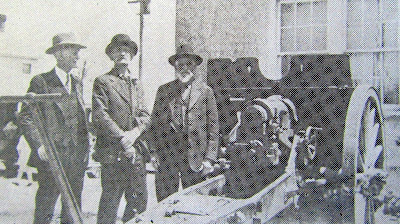

| M.T. Green at Algoma Fuel Co. Coal Dock, 1909 |

Plans were to have coal raised from the boat’s hold with dippers

that could hold about ½ ton. The dippers would be raised and dumped into

hoppers at the top, and from the hoppers carried to cars holding about two

tons. The cars traveled an elevated track to the coal shed. Between the river

and the shed, there was a 100 x 120' cement floor for dumping soft coal.

On November 28, 1909, Algoma was in business. The M.T. Green made history as the first

coal boat to unload at the new dock. Carrying 700 tons of coal, the boat, owned

by the E & M RR & Nav. Co. of Chicago, made big news in Algoma when she entered

Algoma on November 28, 1909.

The following July, the coal dock again made news when the Wyandotte of Wyandotte, Michigan came

into port. Before Capt. William Yates made Algoma, he left part of his 3,000

ton of soft coal - loaded at Toledo - at Manistique and at Sturgeon Bay. The Wyandotte was 377’ long, and the largest

boat to enter Algoma to that time. She had 16 large hatches, two small hatches,

and drew 16 feet of water.

The Green, the Wyandotte and others unloaded in the

next few years and Algoma was in business until the next coal strike.

Note: The lighthouse keeper's home, now a private residence, is visible in the back left corner of the 1909 postcard. Both postcards show the dippers. A close look at the bottom postcard indicates the cars taking the coal to the piles.

Sources: Ahnapee Record, Algoma Record, Algoma Press and notes on the reverse of the M.T. Green postcard in the blogger's collection. Postcards are in the blogger's collection.